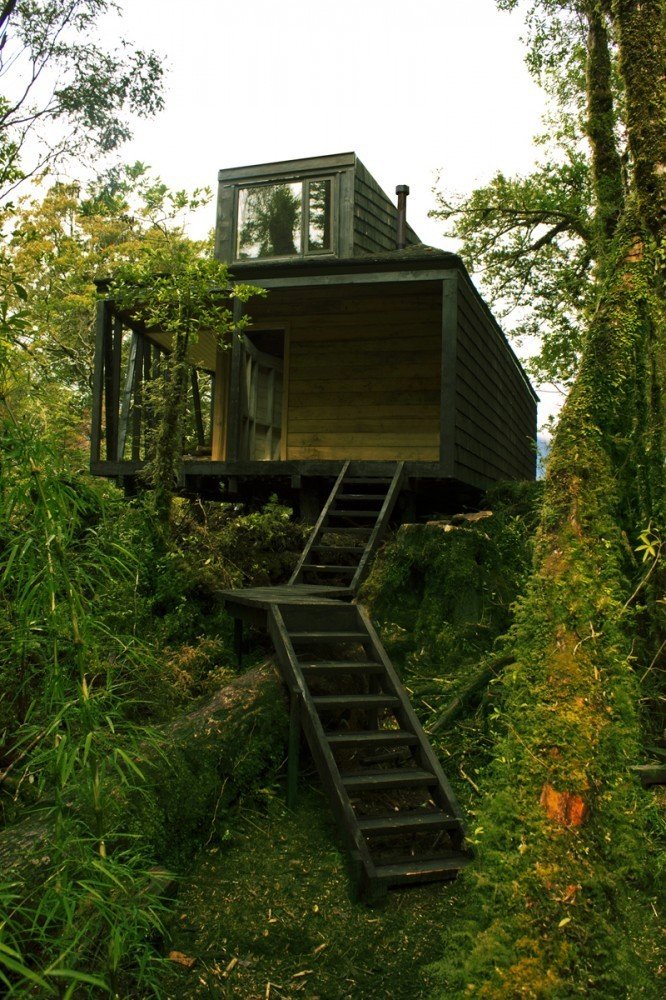

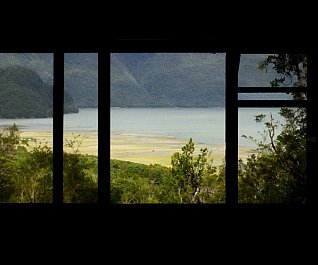

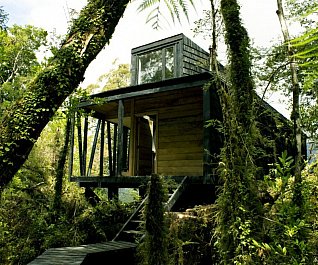

The very tip of South America’s southern cone boasts some of the world’s most extreme landscape. In Patagonia, the Andes weave their way into the continent’s southernmost channels, where frequent precipitation accentuates the densely forested mountains as they plunge into the water. Southern Chile is one of the least densely populated regions in the world, and the lack of human intervention in the environment is evident, so decisions about how to situate the refuge on the land were critical. Connecting the structure to its surroundings was one of the architects’ principle objectives. A 1,600-foot long wooden pathway snakes its way up a hillside thick with native trees, ascending to 160 feet above sea level. The architects selected this site because it was the only place on the slope with enough flat space to fit the necessary program. Approached from the north, the building is oriented along a north-south axis, with the north facade acting as both entry and filter for solar exposure. Visitors move south through a corridor along the refuge’s east edge, which connects several terraces, offering opportunities to pause and observe the surrounding flora. At the south end of the structure, the refuge opens out to optimize views of the Bay of Melimoyu and the mouth of the Marchant River. At the core of the structure is a wood stove which delivers heat to adjacent spaces, reflecting Frank Lloyd Wright’s notion of hearth at a building’s center and connectivity to landscape at the periphery.