GBlog had the privilege of speaking with Ettore Moni, a Parma-born documentary photographer. Moni’s work has been published in Documentary Platform, Domus, Splash, Grab Magazine, Formagramma, New Landscape Photography, Lenscratch, and featured at Parma’s Untype gallery as well as at the European Festival of Photography. With a background in fashion photography and portraiture, Moni currently focuses his attention on Italian landscape and history.

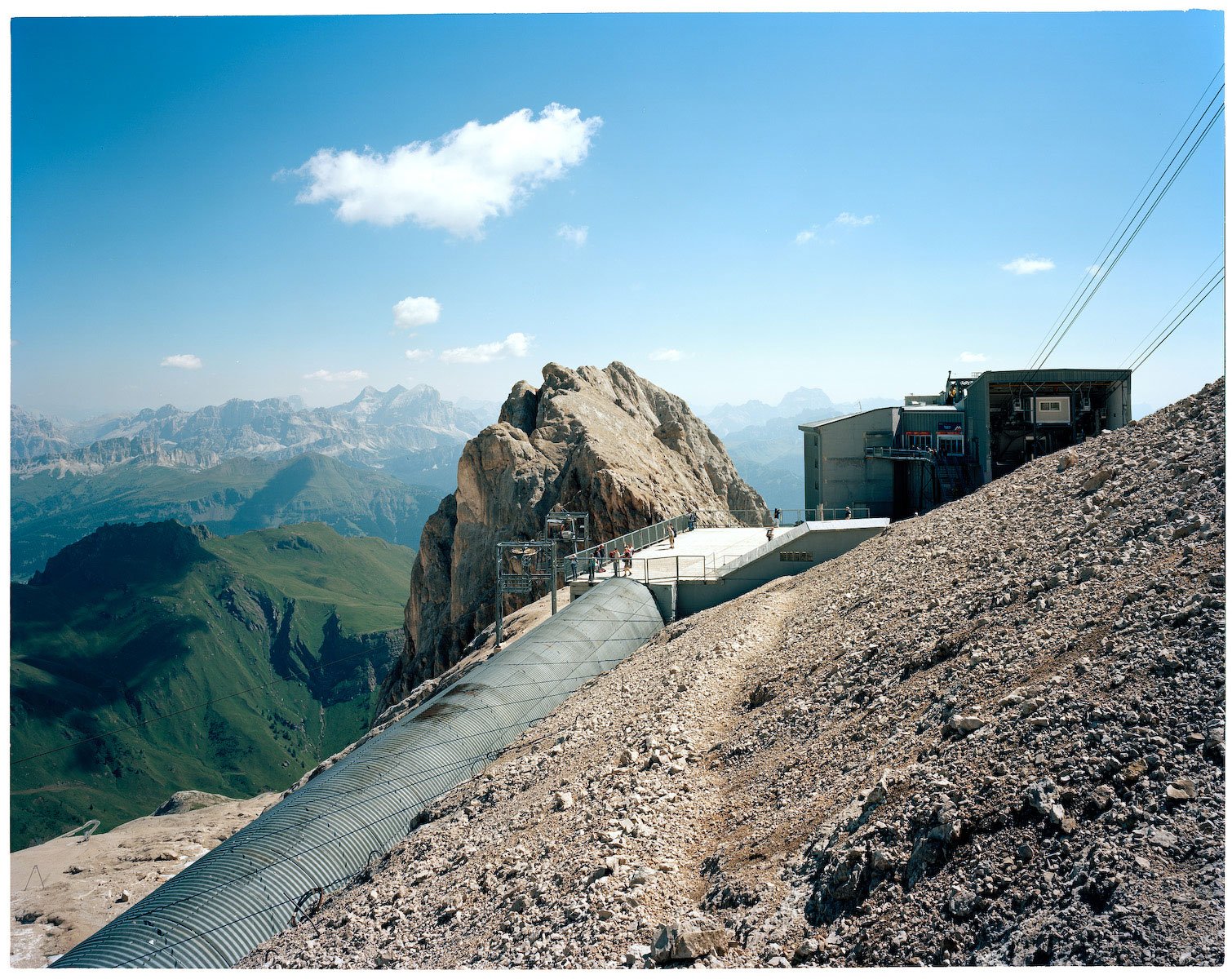

Moni’s most recent venture, Alps, functions as both artistic documentation and anthropological research. The project is a series of color photographs of anthropized mountaintops, in various states of modernization. Moni aims to sensitize viewers to the damage that high-altitude explorers inflict upon the uncharted landscape. Juxtaposing majestic, mountainous panoramas with unsightly buildings, ski lifts and electrical wires, Moni captures the central irony of his project: that humans are destroying the very nature that they intended to honor.

The photography process that Moni prefers is unconventional, and reflective of the caution against perpetual rejuvenation that he expresses in Alps. He uses a large-format camera, shying away from digital models, and applies no post-production to his images. He describes that the way he shoots “is deliberately anachronistic, as if [he] were a member of a species that is almost extinct.”

In Alps, the result is a series of stunning, high-detail images that faithfully capture how we observe the landscape. In the interview, Gessato asked Moni about his unique photographic approach, his emotive and stirring concept, and what he’s thinking about for the future.

Read the interview after the jump.

Before we explore Alps, I’d love to hear more about your technique. What inspires you to work within a traditional framework and avoid digital photography?

I’ve never been interested in the world of digital photography – I still don’t own a digital SLR, but only analog equipment. If I were interested in commercial photography, sports or current affairs, a digital process would be almost mandatory in order to reduce costs and quickly prepare the pictures. But for my purposes, large-format photography is perfect.

It’s a very slow and thoughtful type way of photographing. I have a totally manual machine that is easy to use. Even the exposure has to be done outside. The optical bench does not have anything inside – it’s like a cardboard box with a hole but it has an objective. The process is relaxing, and I think of all the great photographers that have used this technique: Daguerre, Talbot, Nadar, Ansel Adams, Weston, the Bechers, to the more recent artists: Candida Hofer, Burtynsky, Basil, Sugimoto, Vitali, Gursky, Crewdson, and many others.

It’s a photographic technique that has not changed over time. It takes simply knowing how to read the light and have a good eye for framing what you want. I think that at that point I don’t need a digital process. My images are printed directly from the negative (in this case it is called flat film, because instead of having a roll of film, it adopts as sheets of sensitive material. There are no scans or post-production – I would like my pictures to be as similar as possible to what I observe, even though we know that what the eye sees is not exactly what the camera records. I think post-production is required if you have commercial work or if your vision is different from reality, but for me that was never the case!

Do you feel that, aesthetically or conceptually, your approach captures something that digital photography or the use of post-production cannot?

My approach to shooting is definitely different – it’s just another world. With large-format sheets I have to look at the chosen subject through a frosted glass, but have a complete vision of what I want to include or remove in the picture. My eye is in contact with a viewfinder but remains under a black cloth, as was the custom in the eighteenth century with famous darkrooms.

When I am under the cloth the image passes through the lens and flipped upside down. It’s extremely fascinating, and when using a tripod I have time to look at the picture. Everything that surrounds me at the time disappears; I focus only on the image that I see through the lens.

I think that even though digital printing has made enormous strides, printing a sheet film of 4×5 or 8×10 is still by far the best process. The chemistry gives you a result that a digital printer cannot – but this is, of course, just my opinion.

How did the trajectory of your career move from the realm of fashion photography and portraiture toward Italian landscape?

I have always had a passion for photography. I collected photography books, and at the beginning of my career I concentrated on portraits. I really loved Avedon, Mapplethorpe, Penn and Weber, and I did everything from nude photos to landscapes. I tried fashion, but in New York City, my roommate inspired me to dedicate myself to landscape – he returned to Italy and left the realm of fashion. I decided to devote myself only to landscape projects and what interests me deeply.

What inspired you to focus on mountains, in particular?

The ‘Alps’ project grew out of the love I have for the mountains. I like to explore their history, especially the Italian Alps, the scene of so many battles. When I go there I always discover new images – all the works are based on an interest I have in each site.

What was your shooting process like – how did you get to the summits of the mountains to take the photographs, and did those experiences influence your project?

Before I researched information about the places online on the Internet and looked at maps, I chose the highest peaks where tourism has made a noticeable human presence. I loaded everything into my car, and traveled across the mountains from west to east for two months.

When I arrived at a chosen spot, I started looking around me – noticing the cable cars, gondolas, and chairlifts to reach the summit. I met the people who work with them, and explained what I was doing. I walked a lot with my tripod over my shoulder, and this attracted the attention of people who asked me about it. More than once I was photographed, as if I were an alien. Every shot I took had to be thoroughly thought out, because I couldn’t afford to put in so much effort to get to the site, and then not have a clear idea of what to photograph. What I saw certainly influenced my vision!

Your series includes harrowing views of man-made machinery and buildings, but hardly any people. How did you choose to document the modern constructions, but not the people who created them?

The landscapes are wonderful, but my eye have always wandered to where the trace of man’s interaction with the environment is most evident. My images are just witnesses, not criticisms, of what is sometimes positive modernization. Still, I have seen abandoned chairlifts, closed down shelters, and garbage and waste left behind by tourists. I believe we should realize that we should not take advantage of the mountains but respect them. People are not present in my images, only in what they have built, because it is the landscape that I want to capture.

What do you hope your photographs will inspire in their audience – do you hope they will perpetuate change?

I’d like for people to become aware of what is around them, and understand that we must respect nature and wildlife, whether it’s a city park or a beach or a mountaintop. I’m very sensitive to this issue, and it irritates me to see people disrespecting their surroundings! As far as the photos – I think they are just a testimony to this period of time.

What projects are you currently working on, or thinking about for the future?

I have already finished several projects and I plan on publishing them. Sometimes I set off to do one project and I’m attracted to another. I have a series of portraits to strengthen the ‘Alps’ series, and to explore why the occupation of the mountains came to be part of natural history. In the future I’d like to do a project abroad. I have various ideas – let’s see if I’ll succeed!