For Dutch designer Arian Brekveld, who has produced works for the likes of Royal VKB and Droog Lighting, even the simplest and modest designs can speak volumes through their quality and craft. Arian takes this pursuit a step beyond the border – literally so, to Vietnam – with his new collection for Imperfect Design. The collection features Saigon Lacquer, as well as a smattering of ceramic pieces, fabrics, and pillows. Join GBlog as Arian speaks of his travels, his collection, the intriguing process of producing lacquerware, and everything in between!

GBlog: Saigon Lacquer is a truly beautiful collection that captures a traditional craft and presents it with a contemporary twist. How did you first become interested in Vietnamese lacquerware as a platform for your own designs?

Arian Brekveld: Before I went to Vietnam for my first weeks of research, it was just one of the techniques from my list that I wanted to investigate. But actually, I was really excited when I first saw the Vietnamese lacquerware in true form, especially in combination with the process of its making. After the initial visit to the first lacquerware workshop I was very enthusiastic. The quality was superb and there was a sublime level of craftsmanship in the paintwork. What I did not know is that the quality could reach even greater heights; that these designs are, in the end, so beautifully executed is not obvious. I visited at least five workshops in the north and south before eventually starting to work together with the best craftsmen in laquerware.

For those of us who are not as familiar with lacquer art, would you take us through the process of creating a piece? How did you adapt the process to accommodate the visions that you had for the table, or perhaps the Bat Trang vases?

Lacquerware is traditionally applied to solid wood. Nowadays, this is often done on wooden panels, cardboard-like material, and even ceramics. Solid wood is fine as long as the piece does not need to be exported. There are plenty of examples here in the Western hemisphere of beautiful paintwork that breaks in half after a few weeks because the air is much drier and the wood begins to warp. This collection is made of layers of pressed wood to avoid this risk. The shapes are manually made, one by one, on a simple turning device. This result yields a rough shape, which should become smooth, very smooth!

For each piece, a number of layers of a thick substance, a sort of natural fill based on cashew nut oil and plaster, are first applied. The piece then undergoes the following process: drying, sanding, filling, then painting, followed by more rounds of drying, sanding, filling, then painting until there are about 16 layers in total. In this process, the sanding is done with tiny pieces of sandpaper by hand, without the aid of any machines. It takes a minimum of five years before the craftsmen master all stages of the process. As you can imagine, there is a great deal of skill and sensitivity involved in order to achieve the right result. For the final finish, the actual polishing is done with the palm of the hand, followed by the application of a very fine clay used as a polishing paste. … you won’t believe what you see!

Do you have a personal favorite from the Saigon Lacquer collection, or a particular piece that bears great significance?

I think the trays are most special because they show a lot of special opportunities that the technology brings with it. I cannot think of another technique or method of production that would make these items as perfect as they are. The trays have three colors which are seamlessly positioned next to one another. The inner form is hollow, which is only possible if the worker makes the pieces individually and by hand, so that’s special. If production molds were used, these lacquered items would be very complex to make, and unaffordable too. Furthermore, the inside is so incredibly sanded that it almost appears as a liquid. Recently, during a presentation somebody said to me, “Oh what a beautiful dish, is made of plastic?” An awesome reply… her first impression was to think “what a beautiful piece” though she had no idea from which material it was made. That is exactly what is special about lacquerware. If it had been ceramic or metal, you would have recognized it immediately.

We’re interested to learn about your travels to Vietnam, and the ways in which you were influenced by that experience. Was it difficult to reconcile the differences between a Westernized attitude toward manufacturing and the patient, Vietnamese craft?

Good question. It was in fact a real eye opener! I already knew a little about the Asian culture and mentality because my wife and I traveled around there on our bicycles. When you’re on your bike, you see and experience everything. What struck me especially were the agility, patience, and friendliness of the people, which I was fortunate enough to experience again this time. Also, I noticed how driven and loyal they were. For example, I would visit a workshop in the afternoon, discussing various issues and perhaps even leaving them a doodle of an idea I may have wanted to develop. At night, when I returned to my hotel, there would be someone waiting for me, out of breath, with some initial samples, unsolicited but perfect. That’s not at all how things work here in the Netherlands when a designer approaches a company. They will start by telling you what’s not possible and want to discuss production figures and the costs of the models and molds, leaving you disheartened even before anything happens.

Would you describe the experience of collaborating with the Vietnamese craftsmen? Did a common love of good design and beautiful art serve as a shared language and means of communication?

Absolutely! And you need more to realize a good result than your own design skills alone. To a large extent, it’s all about communication. You can’t compare a situation where a designer emails a drawing to one where he checks things out on-site, even in very remote areas. Apart from the fact that that is really appreciated, it provided me with ideas and inspiration. Also, as a designer, I was able to choose the manufacturer for each technique not only based on who I felt possessed the best qualities, but also in terms of local circumstances, or for example, the work atmosphere.

As a designer, I first and foremost looked at the possibilities in all the workshops I visited. And I kept thinking, “if you can do this, you can do that, and perhaps that as well.” Which is how the products developed. They were not thought up in advance and developed come hell or high water just because they were in my head. To me, that’s an approach that I find completely uninteresting!

Looking, communicating and then responding works so much better. The pearls are not there for the picking; you have to trust each other first.

I consciously worked out my designs with the Western market in mind. I don’t mind if people can see that the work has been produced in or inspired by Vietnam. Needless to say, it has been, but that doesn’t have to be too obvious, which is the case with many craft-like collections already on the market.

Apart my communication on the spot, Monique Thoonen of Imperfect Design did a great job of managing all communication remotely. She was the one who gave me this assignment and who developed the concept of sending Dutch designers abroad to develop products together with local craftsmen. Monique set up entire scripts to make sure we used every available hour as best we could. I would like to mention my German Trainee Anna Leyerer too, who helped me a lot in getting everything finished, back at the studio, and in a very short time.

As a designer and creative mind, what value do you see in working with a culturally diverse country? What challenges can you attest to based on your experience with working to produce Saigon Lacquer?

I can say something about that in general terms, and it basically applies to everyone we work with. It is a challenge, or rather a goal, to make sure that things move beyond that. I am above all interested in a sustainable, long-term collaboration with the people we have met there, not just incidents. The collection was designed in such a way that it allows for logical extensions, allowing us to order again from them in the future.

Would you share one of your most treasured memories from your time in Vietnam?

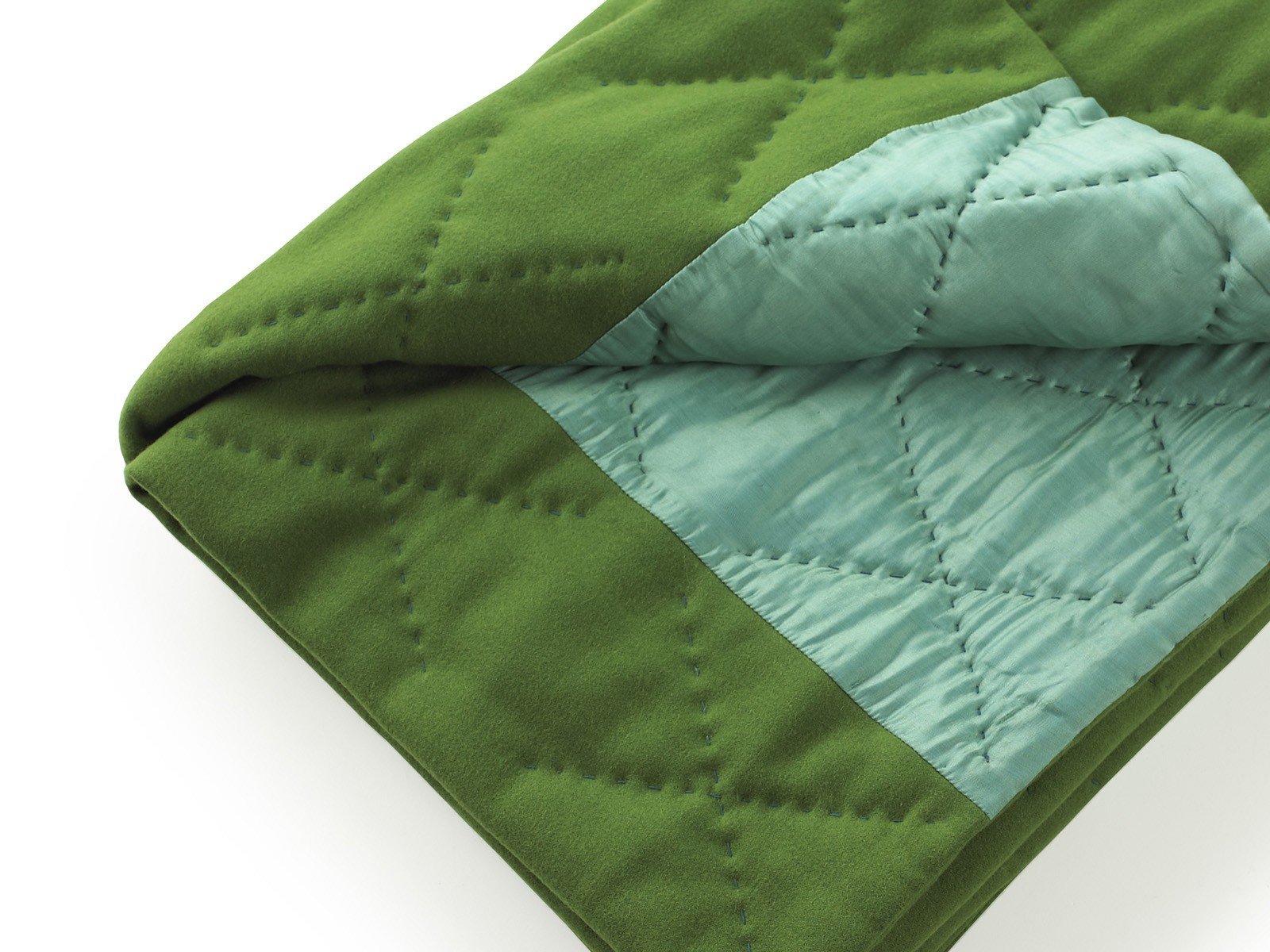

That would have to be my visit to the Catu Group, a group of women in the middle of Vietnam in a remote area. Most of my time was spent around Hanoi in the North and Saigon in the South. Visiting the women of the Catu Group meant planning additional time, additional flights, and long car drives. It was more than worth it to meet these extraordinary women. With simple looms, they make amazing fabrics in which beads can be integrated. The atmosphere was beautiful and there was a serene calm in their simple workshop. The women were in a very good mood and made lots of jokes, which I, of course, did not understand at all. It was a special experience due in part to their friendliness and serenity. Quite a contrast to myself while I was there, with my triple jet lag and long list of questions. For the collection, they made the cushions and fabric for a bag.

Has your recent experience in Vietnam personally encouraged you to explore future opportunities to work with developing countries and creating cross-cultural collaborations? Are there any projects in the works that we can look forward to?

As I mentioned earlier, I expect that expanding the collection will be the first step. Generally speaking, craft is something that is mainly imported. As a student I already visited Dutch craft companies as research for my graduation. I was always the first designer they met! That’s a bit different now. I think that what’s left of it in the Netherlands has been used in such a way that, for me, it is more interesting to explore crafts in other countries. But that can only be done with people like Monique Thoonen, who believe in this approach and who have the guts to invest in new products. So watch this space!

We want to thank Arian for taking the time to share his enlightening experiences, and for allowing us to broaden our own artistic horizons through his journey as a designer. In following Arian’s final words of encouragement, we, in turn, wish to draw attention to Dutch Design Week, coming soon on October 20. The new Vietnam collection for Imperfect Design, including Arian’s work, will be on display at Yksi Expo.